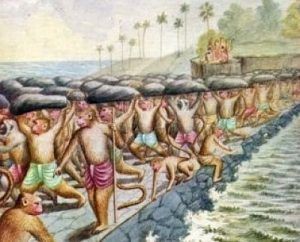

Bridge to Lanka

| Title | Bridge to Lanka |

|---|---|

| Artist | Unknown |

| Date | 1850 - 1860 |

| Size | 127 x 150 cm |

| Material | Natural pigments on cotton cloth |

| Remarks | AM Balinese Collection E74168 |

| Signature | |

| Published | Balinese Traditional Paintings - page 33 |

| Collection | Anthony Forge Collection - Australian Museum |

Rama's Bridge

In the great Indian epic of Ramayana, written several thousand years ago, the author Valmiki speaks of a bridge over the ocean that connects India and Sri Lanka. Rama, the crown prince, was forced to renounce his right to the throne and go into exile for fourteen years. During his stay in the forest, his wife Sita was kidnapped by the evil demon king Ravana and brought to Sri Lanka. Rama organized a massive army that led to Sri Lanka, unable to move troops across the ocean, was advised by the sea god to build a bridge over the water. Rama asks the Vanaras for help in building it, raising a road between the mainland and Lanka, building it with rocks and boulders.

According to legend, the name of Lord Rama was written on the floating rocks, which made the pumice stones unsinkable. The bridge was then used by Rama's army to cross the sea and reach Sri Lanka. This bridge is also known as Adam’s Bridge and India Sri Lanka Bridge.

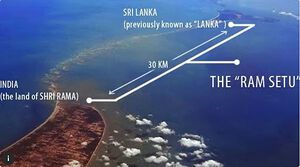

Adam’s Bridge separates the Palk Strait (northeast) from the Gulf of Mannar in the southwest and is 48 kilometres (30 miles) long. Navigation is made more difficult because some of the areas are dry and the local seas are rarely deeper than one meter (3 feet). Until storms deepened the waterway in the 15th century, it was supposedly accessible on foot. Records from the Ramanathaswamy Temple claim that Adam's Bridge was above sea level before a cyclone destroyed it in 1480. You may still see a trace of a connecting strip between the two countries if you look at satellite images of this region today.

In the Hindu epic Ramayana, Nala, a vanara (monkey), is credited as the bridge's engineer. The Rama Setu covers the ocean between Rameswaram (India) and Lanka, which is thought to be Sri Lanka today, allowing lord Rama's army to travel to Lanka. Another name for the bridge is Nala Setu or the bridge of Nala. The construction of the bridge is credited to both Nala and his twin brother Nila and another vanara. The construction project was said to have lasted five days and had a length of 100 leagues. The bridge, once completed, allowed Rama to transport his Vanara army across the ocean to Lanka, with the killing of Ravana and the liberation of Sita returning to India.

The first signs of human habitation in Sri Lanka date back to around 1.75 million years ago: the Stone Age. The age of the bridge is equal to the archaeological estimates. According to Ramayana – the bridge was built in the third age of man or “treta yuga”. The treta yuga or third era of man was estimated 1.7 million years ago. So the time frame cited by Indian legend and scientific reality coincide closely.

Located in the Palk strait, off the southeastern border of India, formed by sand banks, it is characterized by a long and narrow strip of land typically composed of sand, silt and small pebbles. Once this strip of land was believed to be a natural formation, however, images taken from a NASA satellite showed that this formation of land was a long broken bridge beneath the surface of the ocean. Now called “Adam’s Bridge”, it stretches 18 miles from mainland India to Sri Lanka.

More Info:

Bridge to Lanka built by monkeys

Video 1: Could This Be The Legendary "Magic Bridge" Connecting India And Sri Lanka?

Video 2: 1,7 Million Year Old Bridge Built by the Gods - Rama Setu

Kamasan painting - Bridge to Lanka - Ramayana

Kamasan work, on bark-cloth. Probably first half of the 19th century. Obtained from the temple Jero Kapal, in Gelgel. Bark-cloth, usually imported from Sulawesi, gave a good absorbent surface, which did not need the rice paste preparation that was essential for woven cloth, although it is less strong and tends to erode at the edges. This painting has been protected by a cloth strip sewn round the edges, probably in the 20th century. The colours are all local Balinese ochres. The only imported colours used are kincu and black ink, which were imported from China. This suggests that the painting was done before any trade in paints of European origin was established. The work is halus and extremely finely drawn and detailed. It is one of the finest, and very probably the oldest, in the collection.

The episode shown is the building of a causeway from the mainland (of India) to Lanka (Ceylon). The monkeys' work is supervised by Nala. In the centre with a flaming headdress rocks are being passed along from both sides by lines of peluarga and monkeys. The diver animal origins of Rama's peluargo allies are well represented. In the top row of the ridi hand group for example, there is from the left, a monkey face with a sun and moon head dress, a pig face, a deer, an elephant, and a snake. Below them at the extreme right is a man converted into a peluarga.

To the upper left, Rama, Laksamana, Vibisana, and Sugriwa the monkey king, look on up above. Hanoman flies across the strait, and on either side of him, heavenly resi observe the activities below. In the top right corner is a separate scene, bordered by black mountains, the raksasa king, Rawana, receives a report of the approaching army, probably from Shukasharana, with Delem and Sangut behind him.

At the bottom left. Twalen and Morda are as usual not working, but have been catching fish, while various monkeys are shown bathing, riding a turtle, and being eaten by a sea monster.

Across the bottom of the painting is a frieze of animals and one monster (at the far left). Such a panel is referred to as tantri. The painting is remarkable for the use of washes of grey and black, instead of the blue powder colour found in later paintings. Indeed more black is used throughout this painting than was customary later. Another interesting detail not found in later paintings is the little human sirih-box bearer by Rama's side. These details aside, the painting shows all the stylisations and conventions that were still standard a hundred years and more later, and demonstrates the very slow rate of change in this type of Balinese painting.